After growing up in India’s commercial capital – Mumbai, Jamshedpur took me by surprise. The minute I stepped off the train at Tatanagar in February 2015, I knew I was in another world. The station was immaculate with sweepers cleaning with a sense of purpose and vendors selling their wares while keeping their self-respect vest on and not being over-bearing in the process.

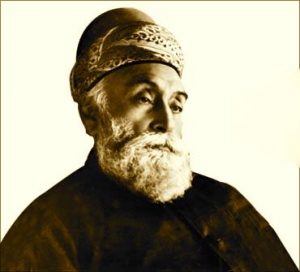

I was witnessing J N Tata’s well laid out plan for enterprise keeping people at the forefront, still viable and working 100 years later.

I was witnessing J N Tata’s well laid out plan for enterprise keeping people at the forefront, still viable and working 100 years later.

The triple bottom line (people, planet and profits) was once the old way …

When a commodity or service changes hands from provider to customer on a small scale, accountability, trust and respect are all byproducts of the transaction. Scale-up of manufacturing and sales brought in more players and steps in the delivery process. When the provider can’t see the customer, other blind spots also creep in. Efficiencies and economics dictate the play over quality. Accountability, service and customer needs can be lost when production becomes the focus.

When I discovered the brilliance of J N Tata, I was relieved to know that bigger and ambitious doesn’t have to mean inconsiderate.

J N – “Be sure to lay wide streets planted with shady trees. Be sure that there is plenty of space for lawns and gardens. Reserve large areas for football, hockey and parks. Earmark areas for Hindu temples, Muslim mosques and Christian churches.”

His motto: To be a leader, you have got to lead human beings with affection.

Tata Steel was a pioneer in introducing a number of firsts in the field of human welfare. All measures were ahead of Indian legislation and several like the eight-hour working day were incorporated by the Tatas before they were implemented in many western nations.

Medical facilities preceded the steel plant and workers participated in management.

And the people J N served while setting up Jamshedpur also fulfilled his dream of India’s first iron and steel plant in 1908.

When money became a problem, J N Tata’s older son Dorabji went to the public for funds and within three weeks had 8000 investors pledge Rs. 2.32 crores (or $23.2 million at that time) to this enterprise.

J N’s cousin and business partner R.D. Tata addressed shareholders in October 1923.

“We are constantly accused by people of wasting money in the town of Jamshedpur. We are asked why it is necessary to spend so much on housing, sanitation, roads, hospitals and on welfare … Gentlemen, people who ask these questions are sadly lacking in imagination. We are not putting up a row of workmen’s huts in Jamshedpur – we are building a city.”

“In a free enterprise, the community is not just another stakeholder in business, but is in fact the very purpose of its existence.

And India’s first planned industrial town established by a Parsi family embodies vision and development while demonstrating socialism and secularism, values that would be spelled out in the Indian Constitution many decades later.